Why I Chose Phonetic Syllabification for Speech Therapy

As a speech-language pathologist trained in a phonetically analytic language, I’ve often found that traditional English syllabification — based on spelling rather than speech — falls short in clinical settings. In my experience, especially when working with young children or clients with speech sound disorders, these orthographic rules don’t align with how words are actually spoken.

To bridge that gap, I’ve developed and adopted a method I call phonetic syllabification — a speech-based approach to dividing words into syllables based on how they are articulated, not just how they are written. While the term is not a standard one in existing literature, it describes a practical distinction that has proven consistently useful in therapy. This page explains why phonetic syllabification can be more intuitive and effective for speech-language therapy, particularly in early intervention and articulation-focused contexts — while also recognizing the value of orthographic syllabification in literacy and academic instruction.

The Challenge: Orthography vs. Articulation in English

English syllabification operates on two levels: orthographic (based on spelling, as seen in dictionary hyphenation) and phonetic (based on how words are pronounced in natural speech). Orthographic syllabification follows standardized rules, such as splitting double consonants (e.g., bottle as bot-tle, happy as hap-py) or respecting morphological boundaries (e.g., un-hap-py). These conventions are invaluable for writing, hyphenation, and teaching spelling patterns, as they signal vowel quality (e.g., short vowel in hopping vs. long vowel in hoping).

However, in spoken English, these orthographic divisions often misalign with articulation. For example:

- In bottle, orthographic syllabification (bot-tle) suggests the /t/ sound ends the first syllable and begins the second. Yet, acoustic and articulatory analysis reveals that /t/ typically serves as the onset of the second syllable, resulting in a phonetic division of [bɑ]-[təl].

- Similarly, in happy, the double pp is written as two letters but pronounced as a single /p/ sound, yielding a phonetic division of [hæ]-[pi], not [hæp]-[pi].

This discrepancy poses a challenge in speech therapy, where our focus is on how clients produce and perceive sounds in real speech, not on how words are written. For children, especially those with limited spelling knowledge, orthographic syllabification can be confusing when segmenting syllables for tasks like clapping or correcting articulation errors.

Why Phonetic Syllabification?

Phonetic syllabification divides words based on their spoken rhythm and sound production, aligning with the maximal onset principle (assigning consonants to the onset of the following syllable when possible). This approach offers several advantages for speech therapy:

- Alignment with Natural Speech:

- Phonetic syllabification reflects how words are articulated in everyday speech. For example, when a child says bottle ([bɑ]-[təl]), the /t/ is produced as the onset of the second syllable, not as a split sound. Targeting sounds in their natural articulatory context ensures precise diagnosis and intervention.

- This is particularly critical for clients with articulation disorders. For instance, correcting a /t/ sound in bottle requires focusing on its role in [təl], not as a coda in bot-.

- Intuitive for Young Learners:

- Children naturally segment syllables based on auditory and rhythmic cues, such as when clapping syllables. Phonetic divisions like [bɑ]-[təl] for bottle or [hæ]-[pi] for happy align with how they hear and produce syllables, making tasks like syllable counting more accessible.

- Orthographic divisions, which rely on spelling knowledge, can confuse pre-literate children or those with literacy challenges, hindering their ability to engage with therapy tasks.

- Relevance to Speech Therapy Goals:

- Speech therapy prioritizes sound production and auditory discrimination. By using phonetic syllabification, we can target specific sounds in their spoken context, improving the accuracy of interventions and client outcomes.

- For example, a child struggling with /p/ in happy benefits from practicing it as the onset of [pi], not as a split consonant in hap-py.

- Support for Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS):

- In CAS therapy, syllable (word) shapes (e.g., CV, VC, V-CV, CV.CV, CV-CV ...)* are used to structure interventions and build motor planning skills. Phonetic syllabification better reflects the spoken structure of polysyllabic words, simplifying therapy planning. For example, bottle is phonetically [bɑ]-[təl], aligning with a CV-CVC shape, rather than the orthographic bot-tle (CVC-CVC), which suggests a more complex structure that doesn’t match articulation.

- This allows therapists to target syllable (word) shapes that match how children produce words, facilitating clearer progression in CAS treatment.

- Clarity for Diverse Linguistic Backgrounds:

- For therapists and clients from phonetically analytic languages, where spelling closely matches pronunciation, phonetic syllabification feels logical and intuitive. It reduces the cognitive load of navigating English’s irregular orthography, allowing us to focus on speech production.

Acknowledging the Value of Orthographic Syllabification

I do not dismiss the merits of orthographic syllabification. It is essential for:

- Pronouncing Unfamiliar Words: Orthographic syllabification helps decode unfamiliar words by breaking them into pronounceable units, such as catalog (cat-a-log) or photograph (pho-to-graph), guiding pronunciation and stress. This is valuable for reading instruction and encountering new vocabulary.

- Literacy Instruction: Orthographic rules help teach spelling patterns, such as how double consonants signal short vowels (e.g., bottle vs. bote). This is critical for reading and writing development.

- Standardization: Orthographic conventions ensure consistency in written communication, such as hyphenation in texts or dictionary entries.

- Advanced Learners: For clients with strong spelling skills, orthographic syllabification can bridge speech and writing, reinforcing literacy goals.

However, in speech therapy, where we typically work with familiar words that clients know or are learning to articulate, the benefit of orthographic syllabification for decoding unfamiliar words is less relevant. For young children or those with limited literacy skills, focusing on written conventions can distract from the core task of mastering spoken sounds.

Application in Practice

To implement phonetic syllabification in our practice, I propose the following:

- Therapy Sessions: Use phonetic divisions (e.g., [bɑ]-[təl] for bottle) when teaching syllable segmentation or targeting specific sounds. For example, guide clients to clap syllables based on spoken rhythm, not spelling, and structure CAS therapy around phonetic syllable shapes (e.g., CV-CVC for bottle).

- Word Bank Database: Update our database to include phonetic transcriptions (e.g., [bɑ.təl], [hæ.pi]) alongside orthographic forms, with syllable shape notations for CAS therapy (e.g., CV-CVC, CV-CV ...).

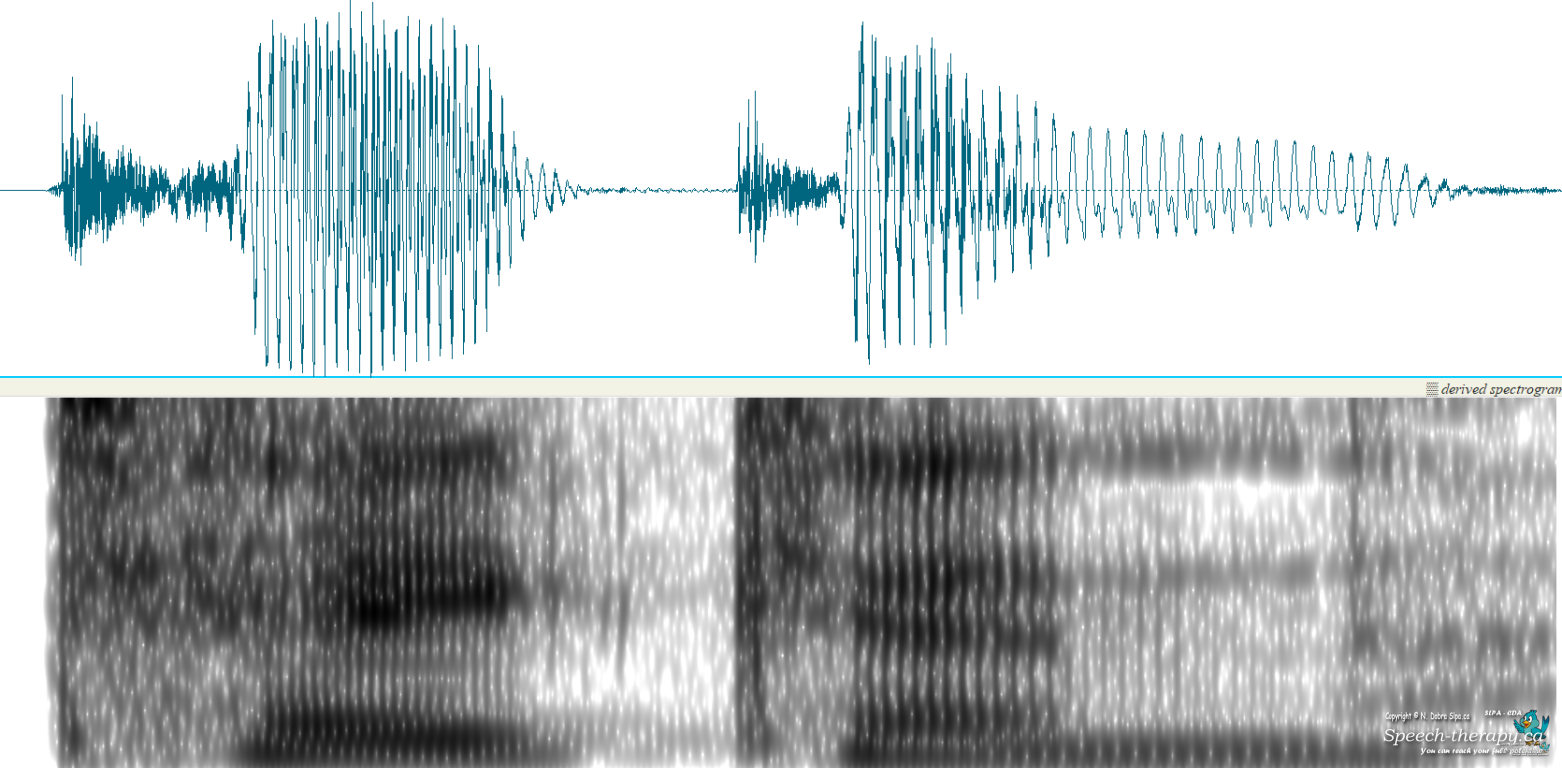

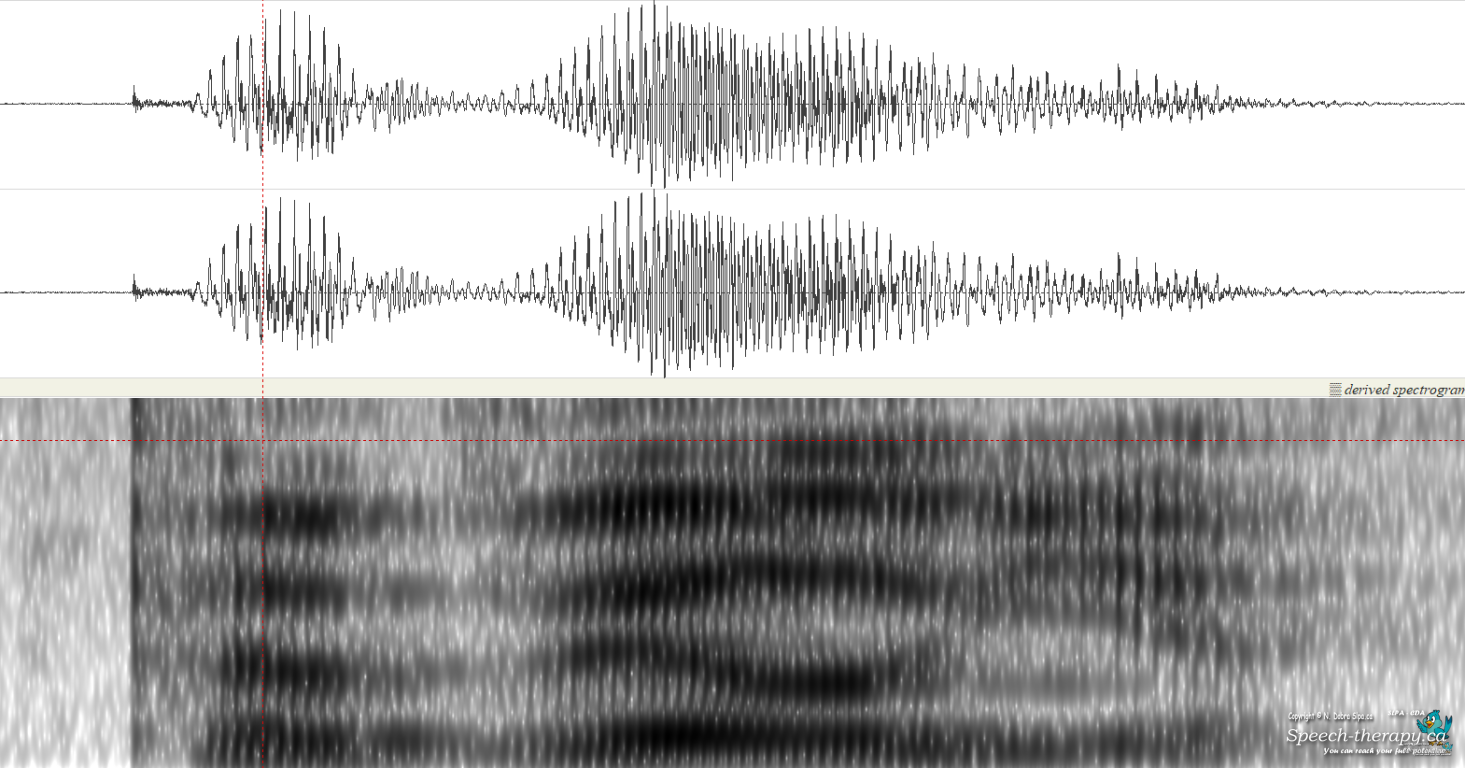

- Literacy Platform: For our online literacy platform, incorporate audio-visual tools (e.g., waveforms, clapping animations) to teach phonetic syllable boundaries, making it intuitive for children to learn through auditory cues.

- Hybrid Approach: For clients transitioning to literacy, introduce orthographic syllabification later, after they master phonetic segmentation, to connect speech and writing.

Why This Matters

By prioritizing phonetic syllabification, we align our interventions with the realities of spoken English, making therapy more effective and accessible. This approach is particularly impactful for:

- Young children, who rely on auditory cues before developing spelling knowledge.

- Clients with articulation disorders or CAS, who need precise targeting of sounds and syllable shapes in their spoken context.

- Therapists and clients from diverse linguistic backgrounds, who may find English’s orthographic quirks challenging.

I have drawn on acoustic analysis and my experience with a phonetically analytic language to develop this method, and I believe it addresses a gap in current practice, where orthographic conventions often dominate. By testing this approach with clients and refining it based on outcomes, we can enhance our ability to support speech and early literacy development.

I welcome feedback from colleagues to ensure this method is clear, practical, and effective. Together, we can refine our practice to better serve our clients and advance the field of speech-language pathology.

Example Analysis: Phonetic vs. Orthographic Syllabification

To support the adoption of phonetic syllabification in speech therapy, we analyze two words: taken, a straightforward example, and pavilion, a more complex case due to its variable syllable structure and articulatory demands. Phonetic syllabification, grounded in articulatory patterns such as jaw movement and the maximal onset principle, aligns with natural speech production, as evidenced by speech spectrograms. This approach enables therapists to target syllable shapes that mirror how clients, especially children with articulation disorders or childhood apraxia of speech (CAS), naturally produce and perceive speech, simplifying intervention and enhancing outcomes.

1. Taken

-

Orthographic Syllabification (based on spelling rules): tak-en

This follows conventional syllable division based on written form, aligning with the morphological structure but not with pronunciation.

- Phonetic Syllabification (Clear Speech): /ˈteɪ.kən/

In spoken English, the /k/ is produced as the onset of the second syllable ([kən]), following the maximal onset principle, as /kən/ is phonotactically valid (e.g., condition /kən.ˈdɪ.ʃən/, connect /kə.ˈnekt/).

- Articulatory Basis: Jaw movement marks syllable boundaries, with each syllable corresponding to an opening–closing cycle (Erickson et al., 2012; MacNeilage, 2008). In taken, the first syllable ([teɪ]) involves a diphthong with a low vowel component, requiring significant jaw opening. The /k/, a velar stop, involves tongue dorsum contact with the velum, creating a closure. The jaw then slightly reopens for the schwa (/ə/) in [kən], initiating a new syllable cycle, though minimal due to the schwa’s unstressed, reduced articulation (Hertrich & Ackermann, 2000). This supports the phonetic division /ˈteɪ.kən/, as the /k/’s release aligns with the second syllable’s onset, creating a clear articulatory and perceptual cue.

- Why /k/ Aligns with [kən]:

Maximal Onset Principle:

English allows /kən/ as a syllable, so /k/ is assigned to the onset of the second syllable for acoustic and rhythmic balance, rather than as the coda of [teɪk].

Articulatory Coordination: The /k/’s closure is followed by a release that aligns with the schwa’s production, linking it to the second syllable’s jaw cycle.

Perceptual Salience: Listeners perceive /ˈteɪ.kən/ as two syllables, with /k/ cueing the onset of [kən], not splitting across syllables as in /ˈteɪk.ən/.

Despite the morphological boundary (take + -en), phonetics overrides morphology in spoken language, as seen in similar words like baking (/ˈbeɪ.kɪŋ/, not /ˈbeɪk.ɪŋ/).

Therapeutic Application:

For a child practicing /k/ in taken (/ˈteɪ.kən/) and other di- or polysyllabic words, focusing on [kən] as a CVC syllable shape mirrors natural speech production. This approach avoids treating taken as /ˈteɪk.ən/, with /k/ in the coda position of the first syllable (CVVC). Syllables like [kən] provide a clearer, more accessible motor pattern for children, particularly those with speech sound disorders affecting sequencing or planning. When targeting /k/ in the coda position, clinicians can use monosyllabic words like take (/teɪk/) or multisyllabic words with /k/ codas. Relying on orthographic syllabification can be misleading in therapy, as it often misaligns with the prosodic and articulatory structure of natural speech. Using /k/ as the onset of a weak syllable, as in [kən] from taken (/ˈteɪ.kən/), simplifies the motor plan and supports clearer speech production, especially for pre-literate learners, as it aligns with the rhythm and articulatory patterns of connected speech.

2. Pavilion (More Complex Example)

- Orthographic Syllabification: /pəˈvɪl.jən/

This follows spelling conventions, placing the syllable boundary after /l/ and before the /j/ glide, reflecting the written structure.

- Phonetic Syllabification (Clear Speech): /pəˈvɪ.ljən/ or /pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/

In careful speech, many speakers reassign /l/ to the onset of the third syllable, producing /pəˈvɪ.ljən/ (CV-CV-CCVC) or, in some cases, /pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/ (CV-CV-CV-CV). Speech spectrograms show the /l/’s formant transitions aligning with the final syllable, with the schwa’s distinct formant structure providing acoustic evidence for these divisions.

- Articulatory Basis:

Jaw movement varies with vowel height, influencing syllable boundaries (Menezes & Erickson, 2013).

In pavilion:

- The first syllable ([pə]) involves minimal jaw opening for the schwa, a central unstressed vowel.

- The second syllable ([vɪ]) contains a high vowel, requiring moderate jaw displacement, less than for mid or low vowels.

- The final syllable(s) ([ljən] or [lɪ.ən]) involve a jaw cycle for the /lj/ cluster and schwa. The /l/ requires tongue tip articulation, aligning with the onset of the final syllable’s jaw opening, followed by the /j/ glide, which involves palatal articulation. In the four-syllable variant (/pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/), the schwa triggers a distinct, minimal jaw cycle due to its unstressed nature (Keating et al., 1994). Spectrograms confirm these divisions (/pəˈvɪ.ljən/ or /pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/), showing clear formant transitions.

- Why /l/ Aligns with the Final Syllable:

Maximal Onset Principle:

The /l/ is phonotactically permissible as part of the onset in [ljən], as seen in words like billion (/ˈbɪ.ljən/). The /lj/ cluster forms a valid complex onset in English, favoring /pəˈvɪ.ljən/ over /pəˈvɪl.jən/.

Articulatory Coordination:

The /l/’s tongue tip gesture aligns with the jaw’s opening for the final syllable, distinct from the preceding /vɪ/, as confirmed by spectrographic evidence showing formant continuity from /l/ to /jən/.

Dialectal Variation:

In four-syllable pronunciations (/pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/), the schwa’s separate jaw cycle creates an additional syllable, highlighting pavilion’s articulatory complexity compared to taken.

Therapeutic Application:

For clients with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS), phonetic syllabification simplifies targeting complex syllable shapes in their natural spoken context. The division /pəˈvɪ.ljən/ (CV-CV-CCVC) or /pəˈvɪ.lɪ.ən/ (CV-CV-CV-CV) aligns with articulated rhythm, allowing therapists to target the /l/ as part of the complex onset [ljən] or simple onset [lɪ]. This approach leverages the jaw’s natural cycle, facilitating motor planning and auditory cues for children who rely on articulatory feedback rather than orthographic rules.

Relevance to Speech Therapy

These examples demonstrate why phonetic syllabification should transform speech therapy practices:

- Natural Environment: Targeting sounds like /k/ in [kən] or /l/ in [ljən] aligns with how speech is naturally produced and perceived.

- Syllable Shape Accuracy: Phonetic divisions (CV-CVC for taken, CV-CV-CCVC or CV-CV-CV-CV for pavilion) match word shape structures critical in CAS therapy, which emphasizes timing, stress, and smooth transitions between syllables (ReST)**.

- Articulatory Alignment: Jaw movement provides a rhythmic framework for syllable segmentation, aiding motor planning and sound production in natural spoken environments.

You are not authorised to post comments.

Comments will undergo moderation before they get published.